But it's also far more complicated.

|

| Amazing Fantasy #15 |

Revolving around the figures of Peter Parker, Uncle Ben, and the Burglar, the narrative would inform every subsequent appearance of the character. Indeed, one could say the 1962 yarn wasn’t only the first Spider-Man story, but also the Spider-Man story.

Despite the definitive stature of Lee's and Ditko’s original comic-cum-moral-tale,

Spider-Man’s lore has undergone several permutations. The narrative has mutated

each time it’s been passed down in comic books, TV shows, and movies. Even Lee

got little details wrong when he wrote flashbacks to the story – a story where

the devil is definitely in the details.

A question arises: do the most well-known retellings of

Spider-Man’s origin story – the blockbuster films Spider-Man (Sam Raimi, 2002) and The Amazing Spider-Man (Marc Webb, 2012) – communicate the same

moral message as the 1962 narrative?

For this fan, the answer is no. I will compare and contrast four important story beats within the original narrative and within each of the films. Then, I will paint a picture of each telling’s wider moral message and give my thoughts on the value of that message.

For this fan, the answer is no. I will compare and contrast four important story beats within the original narrative and within each of the films. Then, I will paint a picture of each telling’s wider moral message and give my thoughts on the value of that message.

WHY PETER DOESN'T STOP THE BURGLAR

|

| Peter's motivation in 1962 |

Peter is motivated purely by selfishness. He resents being “pushed around” by bullies and rejected by girls, so now that he's powerful, he thinks of no one but himself.

In the 2002 retelling, Peter is promised $3000 for

performing in a wrestling match, but the event manager pays him only $100. He

tells the manager that he needs the money, only for the manager to reply, “I

missed the part where that’s my problem.”

When Peter is leaving, the Burglar robs the manager and runs past Peter, who does nothing to stop the thief. When the manager grills Peter over this, Peter spitefully repeats the manager’s line word-for-word: “I missed the part where that’s my problem.”

Peter’s motive here is less selfishness and more

retribution. The implication is that he would have helped the manager, if the

manager hadn't ripped him off. Instead, the manager seems to be receiving his

comeuppance.

In the 2012 adaptation, a convenience store clerk refuses to

sell a bottle of milk to Peter because the teenager doesn't have nearly enough

change. The Burglar then robs the clerk and tosses the milk to Peter, who

leaves. The Burglar flees the store, and the clerk asks Peter for help in

stopping the Burglar. Peter refuses, replying, “Not my policy.”

His refusal appears to be informed by three motives: one,

selfishness – when asked for help, he states that helping is not his policy;

two, retribution – in the wake of the cashier’s penny-pinching pettiness, Peter

turns a blind eye to the robbery; and three, safety – the situation doesn't

allow him to stop the Burglar safely. In this version, Peter is both looking out

for number one and seeking an eye for an eye. However, contrasting with the

1962 and 2002 versions, Peter has no unique opportunity to prevent the

Burglar’s escape.

THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF UNCLE BEN'S DEATH

In 1962’s telling, the Burglar murders Uncle Ben at home,

days after Peter let the Burglar escape. A police officer informs Peter that

Uncle Ben had “surprised” the Burglar, which suggests that the Burglar

attempted to rob the Parker house and was confronted by Uncle Ben.

There's no reason given for the Burglar choosing the Parker house to rob, so its robbery – and thus Uncle Ben’s death – becomes a random event made possible by Peter’s selfishness.

|

| Uncle Ben's death in 1962 |

There's no reason given for the Burglar choosing the Parker house to rob, so its robbery – and thus Uncle Ben’s death – becomes a random event made possible by Peter’s selfishness.

Uncle Ben’s murder in the 2002 film is not random. While

Uncle Ben waits to pick up Peter from the wrestling match, the Burglar murders him and

steals his vehicle. Peter’s failure to stop the Burglar becomes less a failure

to protect the general public from criminals than a failure to consider the

safety of Uncle Ben in a specific situation.

In the 2012 film, Uncle Ben’s death is neither random nor

Peter’s fault. Upon searching for Peter, who has run away from home, Uncle Ben

sees the Burglar and attempts to stop the man.

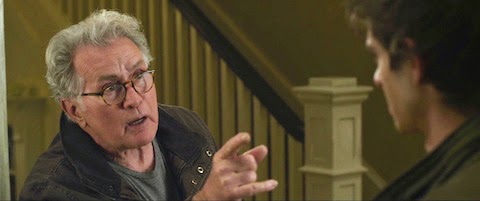

|

| Uncle Ben's death in 2012 |

Although he's on the street because of Peter, Uncle Ben is not in danger until he puts himself in danger – the Burglar is willing to ignore any civilian willing to ignore in kind. Uncle Ben’s death in this version is dependent on his own actions, as he chooses to confront the Burglar.

THE BURGLAR'S FATE

After Peter realizes in the 1962 version that Uncle Ben’s

murderer is the Burglar he let escape, he traps the Burglar in a web and leaves

the man for the police. Peter makes a choice not to hurt the murderer and to

leave him in the hands of the law. In 2002, Peter confronts the Burglar, who

then trips while backing towards a window. He falls through the window to his

death. Peter does not kill the Burglar, or leave him to the police – instead,

it's as if the world serves the Burglar his just desserts. The 2012 retelling

sees the Burglar escape after murdering Uncle Ben. At the end of the film, he

is still at large.

A QUESTION OF RESPONSIBILITY

Spider-Man’s famous mantra first appears in a narration box

in the last panel of his first appearance: “with great power there must also

come – great responsibility!”

In 2002, Uncle Ben speaks the mantra to Peter in their last

conversation before Ben’s death, with some key words omitted. The mantra: “with great power

comes great responsibility.”

This version offers responsibility as an automatic burden on the powerful, whereas the 1962 version offers responsibility as a virtue that the powerful must choose.

This version offers responsibility as an automatic burden on the powerful, whereas the 1962 version offers responsibility as a virtue that the powerful must choose.

Instead of the mantra, 2012’s Uncle Ben says to Peter: "Your father lived by a philosophy, a principle really. He

believed that if you could do good things for other people, you had a moral

obligation to do those things. That’s what’s at stake here. Not choice –

responsibility."

Like the 2002 adaptation, the 2012 retelling emphasizes responsibility as an obligation, not a choice, as the 1962 original did.

MORAL IMPLICATIONS

In the 1962 story, choice is thrust upon Peter Parker. When

he has the power to stop the Burglar and the power later to punish the Burglar,

he must decide whether to do the right thing each time. He is too selfish in

the first instance to make a decision for the greater good, but in the latter

situation, he makes the right decision by forgoing revenge and leaving the

Burglar to the police. Selflessness is the responsible choice.

Because the Burglar could have murdered anyone, Uncle Ben’s

death becomes a metonym for the potential death of the general public. The

moral message is akin to “crime can happen to anyone, so help stop

it when you can.”

|

| Peter at fault in 1962 |

If one accepts that the 1962 world is inherently just – that

Peter’s selfishness did indeed directly cause Uncle Ben’s death – then a far

harsher moral message emerges: “what goes around comes around.” This maxim

emphasizes both our free will and the importance of choosing to live

virtuously. In an inherently just world, one must choose selflessness or

suffer. (More on this idea later.)

The 2002 version muddles both of these moral messages.

First, Uncle Ben’s death is not random. He is killed while waiting for Peter,

when the Burglar steals his car. While it could be argued that this chain of

events is more likely than the original’s, the unlikeliness of the Burglar

murdering Uncle Ben is the crux of the original story (crime can happen to

anyone… including you!). In 2002, Uncle Ben is not a stand-in for

the general public, which makes the story’s message less universal.

If we assume that the 2002 film contains an inherently

just world – which is suggested by the Burglar’s he-had-it-coming death – Uncle

Ben’s murder is paradoxically unjustified. If Peter allows the Burglar to

escape as retribution against the event manager, and the manager deserves

retribution, why is Peter then punished for allowing the world to enact its

natural justice? Perhaps Uncle Ben’s death is not a punishment. The event

manager is punished with robbery for ripping off Peter, and the Burglar is

punished with death for murdering Uncle Ben.

|

| The Burglar falls to his death in 2002 |

Uncle Ben’s death is then reduced to an unfortunate but undeserved event. While Peter may be responsible for Uncle Ben being in the wrong place at the wrong time, his failure to stop the Burglar is not the cosmic cause of Uncle Ben’s death.

The 2002 world of Spider-Man is partly just and partly

chaotic. Some people receive their just desserts, while others suffer for no

reason. The message, then, is to fight chaos. As Uncle Ben explains, when one

is granted power, one is also burdened with a responsibility to selflessness. Justice is

not guaranteed, but a powerful individual has no choice but to seek it anyway.

Uncle Ben preaches a similar message in the 2012 version of

the story. This time, however, the message is never substantiated by the

narrative’s events. Peter is in no position to stop the Burglar without endangering himself, which

makes his other motives of selfishness and retribution irrelevant. Uncle Ben

causes his own death by engaging the armed Burglar in the street. In the drama between Peter,

Uncle Ben, and the Burglar, no one deserves punishment except the Burglar. He

is never brought to justice.

The 2012 Spider-Man world is completely chaotic, which

undermines Uncle Ben’s speech about the powerful’s obligation to do good. If

justice is never served to those who do wrong, why do good?

Some may argue that the 1962, 2002, and 2012 tellings are similar enough. Peter allows the Burglar to escape and then Uncle Ben dies. However, once we look beyond the surface – at motivations, circumstances, the story’s conclusion, and wording – it becomes clear that neither of the retellings capture the 1962 moral message.

Today, the cynical chaos of the 2012 adaptation might be called more

“realistic.” But then what is the purpose of the story’s telling – simply to

describe life as it is? No. All the beats of the original Spider-Man story add up to a moral tale, which

aspires to a prescription: the powerful should choose responsibility, because

otherwise everyone, including the powerful, could suffer.

2002’s message is admirable (we are obligated to seek

justice, even if the world is not always just), but it pales in comparison to

the hard line taken by Lee and Ditko, who attempt to instill faith

in the thought that wrongdoers will get what’s coming to them.

Perhaps that is a naïve thought. But it’s a useful thought. Maybe it’s a thought worth internalizing, if only to help us imagine and understand the potential consequences of our own actions.

Perhaps that is a naïve thought. But it’s a useful thought. Maybe it’s a thought worth internalizing, if only to help us imagine and understand the potential consequences of our own actions.

WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND: A THOUGHT

A new question arises: does the “what goes around come around” maxim give us a real choice between selfishness and selflessness? After all, automatic punishment against the selfish would surely coerce everyone into choosing selflessness. So does a choice actually exist?

The maxim (put another way, “selfishness will harm you”) only emerges from the 1962

Spider-Man story if one assumes its chain of events represents the workings of

some cosmic system of poetic justice. But within the text, that maxim isn’t the lesson Peter

personally learns.

Within the text, Peter's lesson is something akin to “selfishness has the potential to harm you or others.” He knows anyone could have been murdered... but it was Uncle Ben. If Peter time and again were to endanger the public by letting Burglars escape, it might as well be Uncle Ben who dies every time. So why take the risk at all? Why risk the suffering of anyone?

Within the text, Peter's lesson is something akin to “selfishness has the potential to harm you or others.” He knows anyone could have been murdered... but it was Uncle Ben. If Peter time and again were to endanger the public by letting Burglars escape, it might as well be Uncle Ben who dies every time. So why take the risk at all? Why risk the suffering of anyone?

So yes, within the story, a choice does exist. A choice exists because blind

self-interest never guarantees the suffering of one’s self (or even of others). But it does create a risk.

For the reader, the emergent maxim “what goes around comes around” becomes less a hard truth than a cautionary thought. Yes, we do have a choice – and in making that choice, we must believe we’ll reap what we sow.

For the reader, the emergent maxim “what goes around comes around” becomes less a hard truth than a cautionary thought. Yes, we do have a choice – and in making that choice, we must believe we’ll reap what we sow.

No comments:

Post a Comment